If you are like me, you occasionally salivate over the new cameras coming out with high megapixel counts. I look at something like the new Canon 5DS and the Sony a7R2 with a combination of lust and envy. But then I think to myself, “What do I need all those megapixels for anyway?” I convince myself that I don’t need anything more than what I already have. But after that I resume drooling with envy anyway. It cannot be helped.

This has led me to question exactly how many megapixels are needed for great pictures. Will having more megapixels make them look better? Or is it a waste of money? I really didn’t know, so I decided to look into it. The answer, I found, as with so many things in photography, is a sophisticated “it depends.” Mostly it depends on what you will be doing with your pictures. You have to look at the intended output and then back into what is needed.

Let’s take a look at that and see if you really need more megapixels in your camera.

Display on the Screen

These days most display is digital, meaning that most pictures are viewed on monitors or mobile devices as opposed to a print hanging on a wall or something like that. Within the realm of digital display, computer monitors and displays used by Visual Impact productions are the largest and the most demanding in terms of resolution. Therefore, in determining how many megapixels you need for your images, let’s first determine what is needed for maximum resolution on a computer monitor.

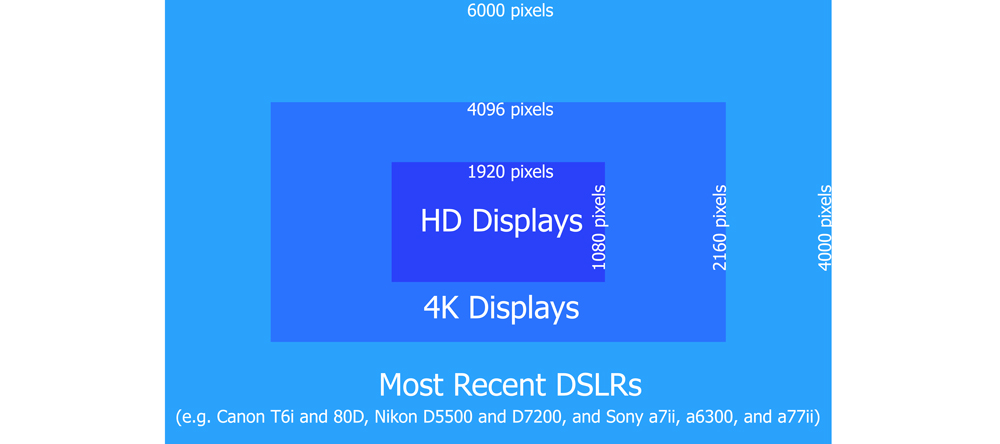

The resolution of monitors is an evolving thing. For some time now, HD display has been the standard to high-quality monitors. HD means that the monitor displays 1920 x 1080 pixels. While HD is still industry standard for the most part, the true latest and greatest is 4K display. That means the monitor displays 4096 x 2160 pixels.

[box type=”info” style=”rounded”]Note that I am going to talk in terms of pixels (length and width) rather than megapixels. It is easy to convert pixels to megapixels. For example, an image 6000 pixels long and 4000 pixels wide is 24,000,000 pixels, or 24 megapixels. The trouble with talking in terms of megapixels is that is overstates differences. Taking the example just used and increasing both sides by 20%, the length is now 7200 and the wide is now 4800. When you convert that to megapixels, however, it comes to 34.5 megapixels (7200 x 4800 = 34,560,000 pixels). So despite only increasing each side by 20%, the megapixel total increased by 44%. It confuses the issue, so I’m going to stick with pixels.[/box]

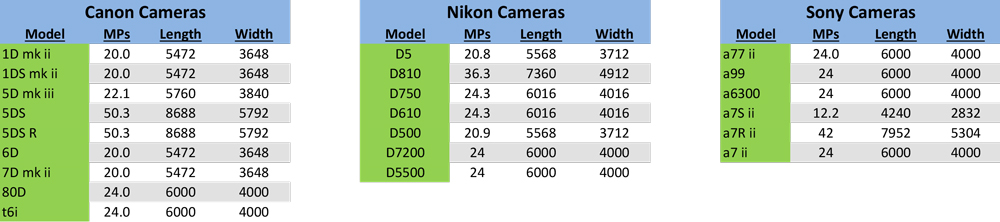

When you compare monitor displays with the pixel dimension of modern digital cameras, you quickly see that there are more than enough megapixels in even entry-level DSLRs and mirrorless cameras to cover the entire monitor display. The most recent cameras introduced by Canon, Nikon, and Sony have generally been 6000 x 4000 pixels, which is much larger than 4K monitors display. These are not the most expensive DSLRs and mirrorless cameras, and in some cases are actually the lower tier of models. Anyway, here is how the most current camera models compare with monitor displays:

In fact, taking a closer look at all the current Canon, Nikon, and Sony camera models on the market, we see that any one of them has more than enough pixels to cover the 4K monitor display:

Based on these numbers, it seems the number of pixels being produced by modern cameras is way more than is needed for any digital display. So are we done? Not quite. There are some other factors we need to consider in comparing image sizes with monitor displays.

First of all, we have to consider the role of the crop. Many of us crop our pictures, which is tantamount to throwing away pixels. If you crop your picture a lot, then you have less data to work with. You could conceivably crop enough to make a difference, at least if the camera resolution and monitor resolution were close. You would need to crop about a third of your picture away before it makes a difference, even compared to 4K.

But there is another perhaps more important consideration. We haven’t thought about whether camera pixels render perfectly as monitor pixels. Apparently, they don’t. We need to keep in mind that each camera photosite is measuring either red, green or blue. To make sure everything is displayed perfectly, in theory you need to drop the resolution to a quarter of the original. However, as I understand it, these differences are very small and will not, for the most part, even be discernible.

Upshot: You Don’t Need More Megapixels for Digital Display

Before making any conclusions about digital display, I should point out how carried away we have gotten when comparing camera pixels to monitor pixels. First of all, we are skipping right over phones, tablets, and other smaller displays on which you might display your photos. Obviously those displays are much smaller and require fewer pixels from your camera to display perfectly. Having skipped over these smaller devices, we went straight to the computer monitor, and not just any monitor. We skipped over all lesser models including the full HD monitor for the 4K display, which nobody even has yet. We are also assuming you would display images over the entire screen, which nobody ever does. And finally, we are thinking about crops and theoretical reductions, etc. The point is that there are a lot of unrealistic assumptions being looked at. We should probably tap the brake here and bring this back to reality.

And the reality is that your DSLR or mirrorless camera has more than enough megapixels to max out any digital display. In fact, nearly all the time you will be reducing the size of the pictures you display. I do it all the time. This website only allows pictures that are 1024 pixels wide. Digital Photography School only allows pictures that are 750 pixels wide (and when I started writing for them the limit was only 600 pixels wide). If you are posting your pictures to an online portfolio site like SquareSpace or SmugMug, then they are reducing the file for you. Don’t even get me started on Facebook, Instagram, and the like, which vastly reduce file sizes. The reality is that for most of us, any standard DSLR or mirrorless camera has more than enough megapixels to max out any digital display.

Bringing it back to the numbers we went through above, we saw that the lowest pixel counts in current cameras are 5472 wide. 4k displays, even if you used the entire screen, are only 4096 wide. That difference gives you some room to crop and reduce. But again the reality is that you will typically use half your screen to display at picture at the very most. In that case, you have plenty of room. Further, if your picture will be viewed on an HD monitor (which is more likely at this point in time), the length of the display is only 1920 pixels, which is barely a third the size of the images being created by entry-level cameras these days. Even if you used the whole screen to display your photo, there is still plenty of room to crop and reduce the photo.

Based on these numbers, it does not appear there is currently any need to chase cameras with higher megapixel counts. Your current camera likely has plenty.

Pixels Needed for Printing Your Pictures

Now let’s turn our attention to printing. The question we need to answer is how big can you print and still maintain a high resolution for your picture. I’m going to get into some numbers related to resolution and print size in a second, but first let me begin by telling you that none of it matters.

The reality is that the larger you print, the further away your intended audience will be. As an example of this, the next time you see a bus with an ad on the side of it, see if you can get really close to it. If you are successful in doing so, you will see that the print quality is atrocious. It will look like dots with spaces in between. But it still looks good from a distance. The intended audience is many feet away, so the picture can be spread out. For us, that means that you can realistically print as large as you want. Even the digital cameras of 10 years ago could print small prints (up to about 8x10s) at reasonably high resolutions. To print larger, the pixels just get spread out further, and that is just fine. Your audience will be further away.

But you want to know how large you can print and still maintain a high resolution for your photos. So let’s get on to the numbers.

What Resolution Do You Need?

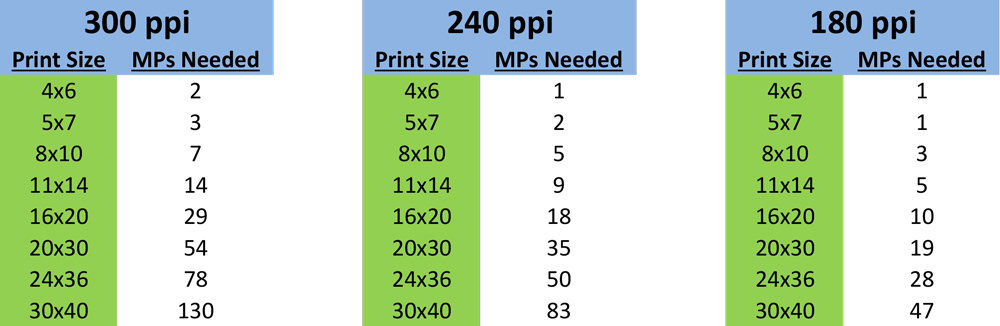

The resolution of your photos is measured in pixels per inch (ppi). This is something you can set in Photoshop or Lightroom. The question is what resolution you need to achieve for the best prints. The answer is pretty unanimously 300 ppi. That is the gold standard for printing. It is what the professional printing labs use. Increases in quality beyond 300 ppi are imperceptable.

Using just this number of 300 ppi, we can determine how large we can print at the highest levels. We just divide the number of pixels in our images by 300. For example, if our camera creates images that are 6000 pixels across, and we print at 300 ppi, then we can create a print that is 20 inches across.

While we are at it, we might as well define “good” and “acceptable” levels of resolution for printing as well. There is no set standard, but the resolution levels I’ve seen used by the online printing labs are 240 ppi as a “good” level and anything above 180 ppi as “acceptable.” If you want to know how large you can print and still maintain a “good” image quality based on resolution, just divide the length and wide by 240. And to see how large you can print at “acceptable” resolution levesl, just divide by 180.

With those levels in mind, let’s just take a look at the maximum print sizes. To spare you the math, I’ve created this chart:

Looking at the chart, you can see that if you have a 24 megapixel camera, for example, which is pretty standard at this point, then you can make prints up to:

Looking at the chart, you can see that if you have a 24 megapixel camera, for example, which is pretty standard at this point, then you can make prints up to:

- 11 x 14 at the highest resolution

- 16 x 20 with good resolution

- 20 x 30 at acceptable resolution

If you are like me, that is about as large of prints are you are going to make. Yes, it is possible that you might want to print larger, but probably unlikely.

Where does that leave us? It is not as clean an answer as I would like, but I think for most people there is no need for more megapixels to make prints. You would have to make very large prints and they would have to be designed for close viewing. If you are making prints larger than 20 x 30, then maybe. Otherwise, you do not need to shell out for the super-high megapixel monsters coming on the market.

Other Factors

Of course, this entire discussion says nothing of the quality of the pixels or even overall image quality. I’m not going to get into that, but I didn’t want to leave it unsaid. More megapixels do not mean a better picture. In the past, when I have looked at low-light performance and dynamic range, I have seen an almost inverse correlation between number of megapixels and image quality.

This discussion also hasn’t mentioned anything about skill or other limiting factors. For example, the quality of your images will have much more to do with the sharpness you are able to achieve than through resolution of the camera. Additionally, there might be other limiting factors as well, such as the ability of your lens to capture sufficient detail to be rendered in the image. This is all to say that, although I am focusing exclusively on the role of the megapixel in this article, there are a lot of other factors you should look to to improve your images before rushing out and buying the latest camera with more megapixels.

The Final Takeaway

The final upshot of this article is – to me at least – that the current batch of standard digital cameras of about 20- 25 megapixels are more than adequate for standard needs. They will max out any HD monitor and even 4K monitors most of the time. They will print plenty big, and even print at the highest resolutions up to about 16x 20 inches. Any higher than that are the viewing distance will start getting larger anyway, such that increases in resolution are not necessary and perhaps even unhelpful.

That said, there is still a place for the high resolution camera. Monitors continue to increase in resolution. We’re at 4K now and who knows what is next? If you have extreme crops and want to reduce the images, then perhaps you might need additional megapixels in order to max it out. And, of course, if you want to create that huge print at maximum resolution, the extra megapixels may help.

I suppose there is no “one size fits all” here, which is to be expected. For me, though, and I suspect the vast majority of photographers, there is no need to reach for more megapixels.

An interesting discussion, Jim, but I’d like to know how you would categorize the images of Peter Lik, who produces the most outstanding images I’ve ever see; they are enormous and designed to absorb you into the scene. You view them from afar, or close up, and the quality is unreal. And the prices are astronomical. He has a website (lik.com) and a gallery in the Mandalay, Las Vegas. It’s worth a visit.

Sure, I’m familiar with him. I’ve actually been to his galleries in Las Vegas and Key West (are you the one that told me about his Key West Gallery?) I really enjoy his pictures as well.

Obviously, he’s a bit of an outlier in terms of the sizing of his photographs. He really goes for the shock and awe with the large sizes. If you are displaying at those large sizes and want a really detailed display, then yes you might need really large megapixel counts. In fact, you would probably need to go medium format (and I believe that’s what he uses) but be warned most of those cameras cost about $40,000. But I still don’t think a camera with really high megapixels is necessary for that.

I think really large photo displays simply require multiple photos combined together later, no matter what camera you are using. As shown in the chart above, for a 30×40 print at 300ppi you’d need 130 megapixels, and I’m not aware of any camera that gets you there with one photo. Plus Lik is often displaying photos considerably larger than that.

You can take multiple photos of a scene and then stitch them together in Photoshop or Lightroom and thereby create enormous files that will support as large and detailed a display as you want. I suspect Lik is doing that (but obviously do not know). But the point for all of us is that you can get as much resolution as you want with any camera if you combine photos in that manner.

Thanks Jim. Great breakdown. I have a few photos I wanted to print bigger but was wondering how’d they look. This gives me a good guideline for the limits of my image. As a side option, if people do want a larger image like Peter mentioned in the comments, I found this article and other links helpful in creating a super-resolution image. I mistakenly tried the process with about 20 images and after Photoshop crunching for about 50 minutes, it created a file that was too-large for Photoshop to save (over 3GB I think). I tried it with 10 images and it made a 2.6GB size TIF that is 10218 x 6590. The JPG was about 30MB at 300dpi.

Thanks Jeff! Glad it helped. The links you mentioned didn’t come through. Can you post again?

Sorry, that’s odd. Here’s a tiny URL for it. http://tinyurl.com/jcu27ng