We all know the sky during the day is blue. We know that clouds are white (or grey). And we know that the sky can turn different shades of yellow and orange at night. But why?

When you are photographing in the outdoors, the sky is such a huge part of your pictures that it pays to have a little understanding of what is going on. So in this article we’ll talk about why these colors show up – and why others don’t.

But don’t worry, I will keep this as simple as possible. After all, we are photographers, not scientists.

Why is the sky blue?

The main thing to understand is this: the color we see in the sky is caused by light getting bounced around by the earth’s atmosphere. If the earth didn’t have an atmosphere, light would just travel straight to the earth. We would still be able to see things around us (as long as we could see the sun), but the sky would just be black.

Light comes from the sun in different wavelengths, which correspond to different colors. The longest wavelengths of visible light are reddish, and the shortest are blueish. The shorter wavelengths (the blue ones) are more susceptible to getting bounced around in the atmosphere.

As light enters the atmosphere it starts colliding with different particles, the nitrogen, oxygen, etc. The long (reddish) wavelengths just continue on in a straight line toward the earth. They are large enough to fight through the air molecules without disturbance. The small (blueish) wavelengths, on the other hand, get bounced around.

So here’s what you should understand: there is nothing in the sky that is blue. What you are seeing is the blue part of the sunlight that is deflected from its path to the earth by the molecules in the earth’s atmosphere. Since it is deflected, you see more of it in the sky.

Have you ever noticed that when you photograph a wide landscape from a scenic vista the things in the distance take on a bluish cast? If not, go back and look at some of your old pictures and you will doubtlessly see it. The cause of this phenomena is the same: there is a lot of deflected blue light between you and that distant horizon.

Why are clouds white?

This same scattering phenomena also explains why clouds are white. Remember that ordinarily the short wavelength (bluish) light gets bounced around on its way to the earth, while the long wavelength (red) light powers through those same molecules because it is larger. That’s why we are seeing blue in the sky. But now, when those light wavelengths run into clouds, they are hitting larger molecules, so none of the wavelengths can fight though it. So now all the light wavelengths are scattered equally.

In other words, there is no color cast because we are seeing the full range of wavelengths in the light from the sun. When you mix all those wavelengths together, what we see is white light. Without a cloud, you are seeing some of the wavelengths more than others, and the result is blue. But now with a cloud in the picture, you are seeing light equally scattered, so you are seeing all of it equally. The result is white.

This same phenomena also explains why a hazy day makes everything in your picture appear white and washed out. On a hazy day, the light from the sun is hitting water molecules in the air. Those water molecules are larger than all of the wavelengths of light, so all the wavelengths are scattered. When you see all the wavelenths equally, the result is white. So the haze comes across as a white or washed-out cast to your photos.

Why is the sky red/orange at sunset?

When we look towards the sun at sunset, we see red and orange colors. Why is that? What happened to all the blue?

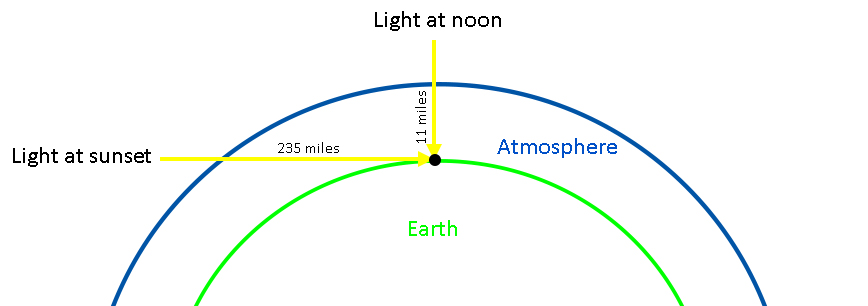

At sunrise and sunset, the light has to travel much further through the earth’s atmosphere in order to reach you. In the middle of the day, the light travels through about 11 miles of atmosphere, but at sunset the light is traveling through 235 miles of atmosphere. The long wavelength (reddish) light still passes through the atmosphere, and the short wavelength (blueish) light is still getting bounced around. Except now it gets bounced around about 20 times as much. During this journey, much of the blue light gets scattered out and away from the line of sight. So now we see a lot more reds and yellows.

The Upshot for Your Photography

Many of us are “natural light” photographers. That is, we don’t bring our own light sources, but rather take the light as we find it. That being the case, it pays to understand why the light acts like it does. It will help you understand, and potentially counteract, the blueish hue you get in many pictures taken during the day. It should also give you a little bit of extra help considering locations to photograph, as you’ll be able to better visualize what the final picture will look like.